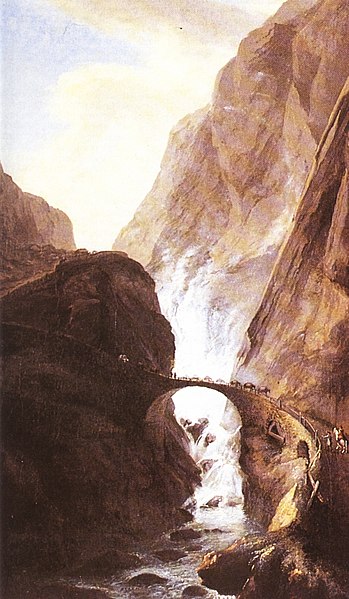

Swiss painter Caspar Wolf was known primarily for his landscape paintings, those with the Alps to be precise. Wolf’s imagery of glaciers, waterfalls, caves or creeks are epic, and so much so that with the aid of the grey tone of colourisation in his paintings, those natural formations seem cold and impervious- a lurking hostility that welcomes not the viewers’ ready absorption. One can imagine standing before a grand painting by Wolf and not awed by its overwhelming magnificence but woefully dwarfed by its monstrosity.

Seen here the 1777 painting titled, Devil’s Bridge in the Schoellenen. A

precipitous bridge straddles between the gorges, which magnitude dominates the

majority of the canvas, and reduces the sky to merely a conical view. A

rumbling stream of water races to its still pool, and the boisterous spirit

within, reluctant to be transmuted abruptly to insipid sedateness, bubbles still

white and frothy. I am immediately reminded of the great Flemish landscape

painter, Joachim Patinir, who was famed for turning landscape, the usually

bit-role in the theatre of allegorical paintings, into a singular genre. Take

for example Patinir’s Landscape with the

Flight into Egypt, which particularly shares a slight resemblance to our

painting, the figures are as well minimized by the unpleasantly barren rocks

and the picturesque landscape that stretches afar.

But Wolf’s landscape certainly provides a

more unnerving view. The travellers, possibly trudging up to the summit, and

down through all the creaks and crevices untrammelled, suddenly encounter this

bridge, which, thanks to the white vapour of the waterfall, is made only dimly

visible. One can almost feel the palpitation of the travellers’, when the

deafening din of the rushing water only contributes to their growingly fainter

hearts. Finally, an audacious one takes a tentative step on the wobbly-looking

bridge, and nimbly he crosses to the safe side all in one breathe. Triumphantly

the victor raises his horse and beckons his companions to come trotting through.

For me the painting is an embodiment of

courage, a whipping-up of the collective morale, and a shaft of hopeful light

through the heavily encompassing mist of desolation and danger. It is also a

pictorial evidence of the underestimated power of men, which is often

preternaturally augmented when facing their toughest moment.

But here I raise my question, why are

landscape paintings invariably one of the most undervalued amongst the others? The

old maxim proves right, that nature is the best teacher. Stories and lessons

abound in nature. It is when witnessing nature’s ingenious creations before the

artist’s hungry eyes that his work breeds the richest fruit. But is it not

weird that although nature guarantees the grandest, when enslaved and

imprisoned by the artist the viewers are then granted the private view of

nature- curiously, in its patronizingly blinkered vision.

Comments

Post a Comment