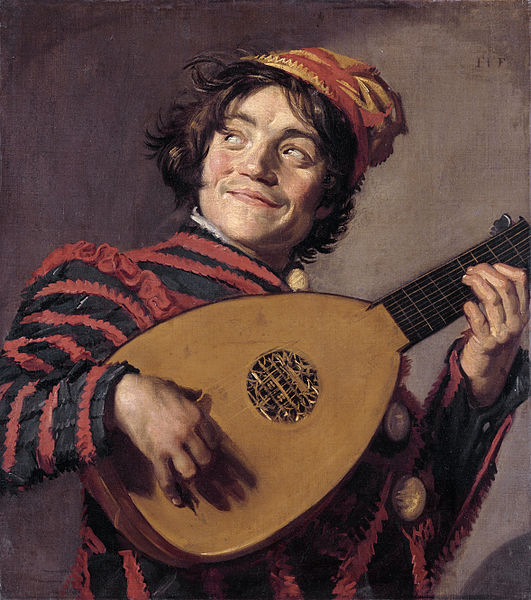

Very rarely are Frans Hals’ people appeared

without cheerful countenances or unpretentious smirks. Happiness reigns Hals’

portraits of people of his time, the aristocracies and the peasants alike. It

therefore came not as a surprise if music should be served as an instrument for

the paintings’ permeation of felicity. The buffoon in the picture has himself

dressed to the festivity, gleefully plucking away the lute, glances sideward as

if to engage the attention of the apple of his eye, whom the music is dedicated

to. What makes his music tangibly and palpably felt is the tresses of his hair,

which scamper about joyfully in midair.

From centuries on painters have tried to materialize

the infectiousness of music among the listeners. Or the essence of music could

be rendered with ingenious exactitude, as seen in Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432), in which some

art historians alleged to identify the precise notes of the music solely

through close study of the angels’ humming mouth. In most cases, the aim is more

or less achieved when the painting succeeds in suggesting the elements or moods

of music. The music in our painting is not one for a raucous affair, but

appealing to a knot of selective listeners. This private pleasure, permissible

only to a few, is also manifested through Edouard Manet’s Spanish Singer (1860). Posing against a dark background, the

Spaniard plays solitarily to himself, with merely the enveloping darkness and

empty tankards for company. But the singer is not unheard. Thanks to Manet’s

dexterous treatment of light, which comes from four winds and fixates on the

singer, and makes him the lodestar of the stage. His figure is also enlivened

by the juxtaposition of complementary colours, and also his silhouette, looming

just beneath his tilted feet. Manet’s music is something more profound;

something that invites contemplation.

Back to our painting. For a long time I had

pondered the possibility that it was not sheer happiness that Hals was trying

to capture. On hindsight the smiles of his people almost seemed satirical, or

feigned, as if the sitters were ordered to pull on various comic expressions. What

contributed to my notion was also the often garish colours applied to the

features, which made the panoply of faces not always delightful sights to

behold. But Hals prevented any unpleasantness of his portraits by doing his colours

in visibly loose brushstrokes, as if the paintings were all following the

rhythms of some unknown melodies, and the painter, basked in the beautiful

symphony when completing his masterpieces.

Frans Hals’ people are like clowns, the

professional ones who are playing the roles exactly as they are assigned to be emulating.

Any attempt to scrutinize them psychologically is difficult, and almost

impossible. Hals’ people are impervious to any apparent emotions, and always

smiling their masks are untearable. But the mood and feeling is in the

atmosphere, as in Buffoon Playing a Lute

(1623-4), the sound of music is realized. Anyone unimaginative who is still

unable to conjure up the substance of music should eschew Matisse’s Music (1910), which makes the spirit of

music an even more abstract and ungraspable entity.

Comments

Post a Comment