The story of Judith beheading Holofernes reveals

more violence than female heroism. Paintings or sculptures often depict Judith carrying

triumphantly the head of her victim, in a fashion of the notorious Salome. Or she

can also be seen stepping suavely on Holofernes’ head, like that in Giorgione’s,

in which the heroine leaves her majestic beauty and elegance untarnished even

when carrying out the bloodiest business. The pervasive serenity of Giorgione’s

painting only augments the lurking horror.

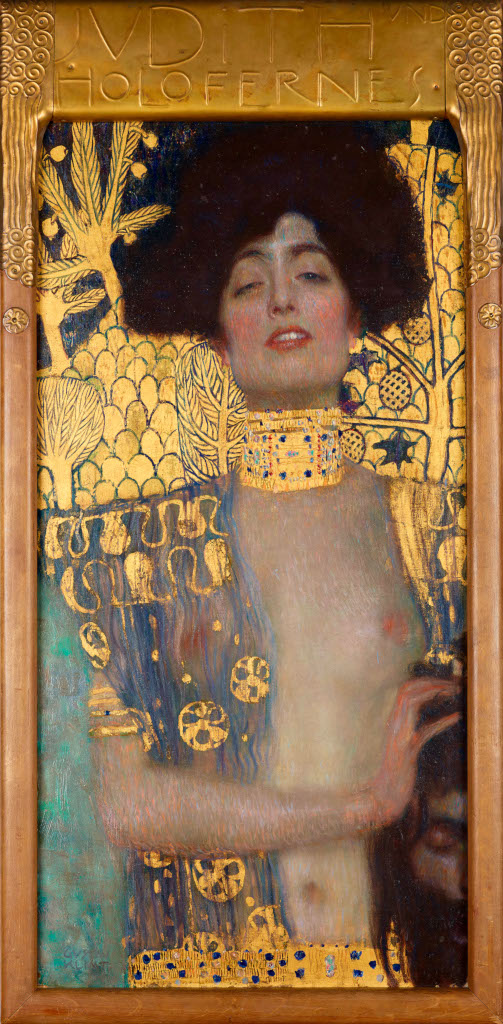

Gustav Klimt whips up a different degree of

horror in his depiction of the tale- the kind of horror that, at the sight of the

painting the viewers blush. Or they might constantly dither between evading

their furtive glance and transfixing boldly their eyes on every telling detail.

In Judith I (1901), Klimt introduces

a rare sentiment- that of an unreserved sexuality, which contradicts brazenly how

Judith was originally portrayed- a widow with unquestionable virtue. Klimt’s

Judith is modernized as a high-class prostitute, luxuriously adorned with gold,

parting her dress like drawing up curtains- most probably a suggestive gesture

of inviting in her guests. The viewers can only get a blurry, partial view of

Holofernes’ head, squeezing into one nook of the canvas in shadow. Instead, the

head of the heroine is in focus, emphasized especially by her bobbed hair. And

with her chin slightly up, her sultrily squinted eyes collide with ours.

Judith’s facial expressions suggest ecstasy-

before love or after love, and also in pain, as that feeling is often

inextricable with ultimate excitement. But rarely is this ecstasy accompanied

with murderous act, at least not so without hints of malice or wiles. Those

eyes can seem conspiratorial, yet they dwell upon sexual enticement. And so

thus the head of Holofernes suddenly becomes a mere appendage of the murderess,

like a handbag she never leaves without.

I was thinking about Edvard Munch’s Madonna (1894) when I first saw Klimt’s

Judith. It is the selfsame absorption in intoxicated passion- but Munch’s

Madonna reaches its apotheosis; her lucidity and consciousness at great risk of

dissolving along with the approaching whirl, soon to be abandoned. What both

painters also share is their blatant bastardization of subject matters that are

best to be treated with undiluted reverence and exactitude. The concurrence of

sexuality and sin in Klimt’s Judith, and the rush of intoxication and love when

overcome with elevated holiness in Munch’s Madonna. Those contrasting emotions can

meld together in the blink of an eye. It is the marriage of Hell and Heaven.

What Klimt contributed to other successive

art movements, as represented with our painting, was the realistic delineation

of human nature, the delving-into of the complexity of one’s psyche. Klimt’s

paintings are a display of various performances of human emotions, the

maddening theatre that inclines to put on plays that confront our innocent

sights, but manage to ingrain in our memories evermore.

.jpg/461px-Edvard_Munch_-_Madonna_(1894-1895).jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment