Some like to paint their world in soft

colours, like those in an Impressionistic painting, in which the scenery is

always pleasant, tinted with blossoms here and there, and everything is swathed

in a gentle haziness seen regularly on a beach resort. For those the world

cannot be a better place. Their days can be fairly uneventful if they are

unimaginative enough not to be bothered by any uninvited incidents that might

put an abrupt termination to their comfortable monotony. The opposite of an

”impressionistic” world is by no means a world of complete black-and-white. I

never believe anybody can have a life so utterly devoid of colours, given the

fact that today we are living in a turbulent world, anything surprising or

incidental can seep into our days despite how hard we try to keep them mundane.

A world of garish colours is what I suggest as the opposite of a world of

pastel-softness. It best represents the extreme emotions of mankind, be it

anger, excitement, amorosity, desperation and so on. As much as I am fascinated

by some painters’ wilful use of colours, those paintings or artworks leave me

an impression of cold disquietude.

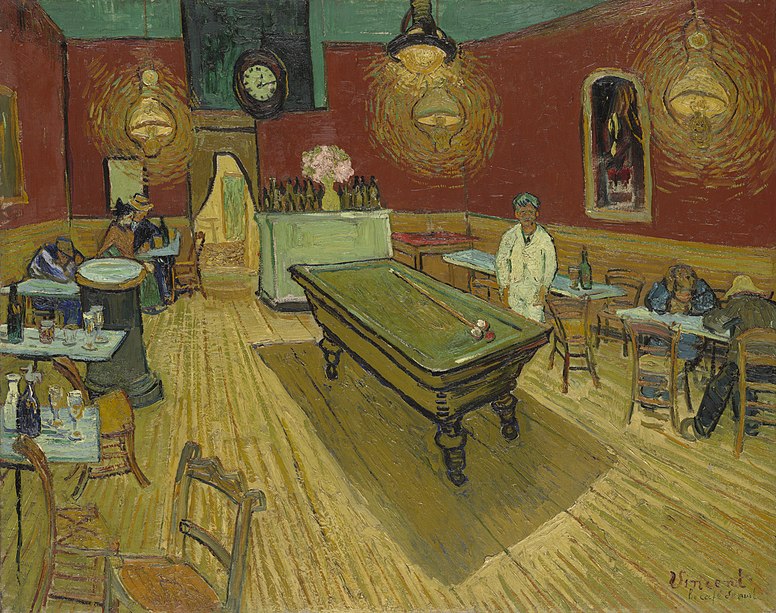

The

Night Café (1888) is what Vincent van Gogh once

considered one of his ugliest paintings. The painting is teemed with contrasting

colours: bright green, emblazoned red and gleaming yellow. The

café looks not like a place for leisure but more like, what Van Gogh intended

it to be, a madhouse. Besides the blatant colours one’s anxiety is compounded

when seeing the yellow floor extend itself and approach towards the viewer. The

hospitality of seemingly wanting to share intimacy with the viewers is not a

comfortable one, not so much as that in those sacra conversazione pieces, in

which Madonna and the Child are mostly placed on an elevated throne, and from

it the carpet cascades and threads its way towards the viewers, inviting them to bear witness of this holy

ceremony. The floor in Van Gogh’s is more like the golden brick road, but a

golden brick road that leads not to a promising glory. Instead, within the

picture frame, the loungers are cooped up in their solitude.

William

Eggleston’s photography is an honest record of the banalities of daily lives.

Disquietude and anxiety stemming from loneliness are augmented by the exaggeratedly

vivid colours; regardless of how boisterously those colours assert themselves a sense of sparseness characterises Eggleston’s photographs. The

work, Untitled (1975), reminds me of

John Everett Millais’ Ophelia

(1851-52), for both heroines lie supine and resign their lives to nature- an

evidence of how eerily mankind resemble or blend into its surroundings. I sense

a vortex of hallucination surging out of the girl’s body, even when she is

lying in complete stillness. Its bright colours, so bright that I am convinced

the sunlight is also immortalised in this photograph, also contribute to the

work’s overall giddiness. Different from Van Gogh’s claustrophobic Night Café, a world peopled by colours

in Eggleston’s photography is ever-expanding, and this expansiveness can be

unnerving.

What will happen then if the garish colours

all join the vortex of hallucination and everything run amok on the canvas? One

might want to mention Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionist paintings but

the masterful Pollock seemed always manage to rein the haphazard pictorial

elements into harmony- neither colours nor lines or patterns are permitted to

claim as the singular star. Polish expressionist painter Feliks Topolski’s

portraits are evocative of the explosive, destructive mess of Francis Bacon’s. Human

figures are barely discernible save that of the diverse use of colours. In

Topolski’s Portrait of T.S. Eliot (1961)

it is the red that stands out amongst the others. The red of Eliot’s robe is a

violent red, which portrays the poet more like Count Dracula, dressing in the

blood of his victims. Like Bacon’s, Topolski’s sitters have their figures and

identities undermined in the portraits, as if everything will soon peter out,

leaving only the mass of colours and lines.

Or maybe the colours and lines will

eventually fade away. In this case the garish colours are the intruders that

disrupt the peace and harmony of a vapid world, but they are not unwelcome,

they can easily become the essentials that make a painting more interesting. As

one gazes long enough at a conglomeration of garish colours giddiness ensues.

Little do we know it is the moment when we are unconsciously transported- into

the painting, into the colourful mess and into the eternal swirl.

Comments

Post a Comment