When I gaze

at the word, its formation of letters renders it an uncanny oddity:

“grotesque”- one that comprises a lot of twists-and-turns. One always draws

towards the grotesque without reason- perhaps it is how we express our delights

of spotting something markedly different amongst the other homogenous hogwash.

The commonplace bores us.

Nevertheless,

those who make it a purpose before out seeking for the grotesque often find

themselves land in with the shams. The real grotesque is not wholly stripped

off its normalities. According to Sigmund Freud’s “The Uncanny,” the uncanny

belongs to the ones that bear the most resemblances to your own selves- those

are virtually the images you stare into the mirror and find it smiling back at

you, a smile that conveys both malice and mystery, a smile that is foreign to

your mundane understanding. It is an odd fact that I’ve never got along well

with twins and usually I like to scrutinize them piercingly, in hope that any

second one of them will yelp like a beast and the other will respond with a

scowl of astonishment. Someone has broken the rules.

In light of

skewing the image of reality, no one does it more astoundingly as Otto Dix. The

German painter loved to wrong-foot his viewers. His portrayals of the

upper-class society are unapologetically ugly. In Großstadt Triptychon (1927-28) the revelers seem to be seized by an

unnameable disease: they all seem bald (those are more likely wigs than real

hair); the heavy make-ups can hardly conceal their looming debility: livid

skin, sallow cheeks. Maybe the triptych is merely allegorical, as what most art

and literature were during the war period. The party-goers are in a drugged

state of reverie- they are either the marionettes we gawk at a puppet show or

the actors on stage. There is only a thin line of difference between reality

and uncanny when, unexpectedly, the footlights suddenly assault you.

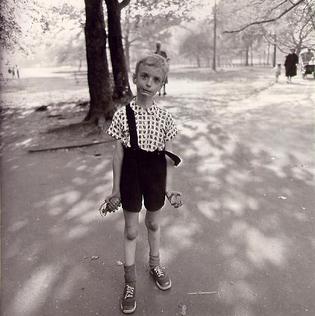

But it was

Diane Arbus’ photography that first came into head when researching for this

piece. The Identical Twins (1967) is

undoubtedly an obvious example but the one that always grips my attention is Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park

(1962). The little boy strikes a pose that is only analogous to an offended

cockerel: he stands gangly about, hands claw-like, and a strap hangs loose

which seems to signal an imminent transformation from human to beast. This

photograph is also a vivid demonstration of how “unsettling” reality can be. And

again, it also illustrates the power of performance- how one can easily turn

grotesque simply by acting.

Things can

also seem grotesque even when no deliberate change is made to them and nothing

unusual is taken place. Installation art is one of these grotesque forms of art

since so many factors can mystify a normal piece of work, be it the setting or

the different angles the viewers are perceiving the work. Marcel Duchamp’s is

the most prosaic one can ever conceive, if not slightly indecent as an art

piece- a porcelain urinal the artist archly named Fountain (1917). Duchamp kept the urinal unadulterated and simply

reoriented it 90 degrees from its normal position. Myriads of visions dance

before my eyes when I gaze long enough at the urinal, and none of them are even

remotely related to it. Imagination often comes in the strangest form.

But how

grotesque it is when, at times, you must abide certain rules to carry out to

things you want to do. There are people and places that make the whole world a

horrendous custom service in the airports. Every corner you turn you meet the

sharpest thorn. But the mavericks carry on, even when they are the loners on

their quixotic journeys they sally forth. No one knew before that a fragile

butterfly can change weather, and when the new knowledge is finally dawn on

them the hurricane is above their heads. And eventually, nothing is grotesque

anymore.

Comments

Post a Comment