It is all

about putting your best face forward. Photographer captures the fugitive moment

before it flees. Painter, like an envious sister of Photograher’s, constantly

resents the ephemeral existence of a mesmerising smile, which often freezes into

a stiff, twitchy line even before she applies onto the canvas a tentative

stroke. But one day as Painter is doing half-heartedly another portrait and

racking her brain trying to recall what ingenious sparks of spirit that just

seconds before flash across the sitter’s otherwise stoical face, her paintbrush

takes a sudden and willful sweep over the canvas, leaving a faint but

perceptible line on the person’s forehead. Disgruntled at first when Painter

sees what a careless mistake she has compounded with her clumsy toil, but then,

after assessing the screwed portrait at several different angles, a mischievous

smile plays upon her lips.

The sitter

remains the same throughout the process of painting but the authority belongs

to the painter, who holds the destiny of the sitter’s effigy firmly in his

hands. How joyful it is to paint an unappealing portrait of your nemesis!

Painter savours the inexpressive elation when one day she does a portrait of

her aloof sister, Photographer, on the sly and successfully renders her an unprepossessing

snob. In the end of the day Painter has a fitful night of sleep, incessantly disturbed

by her own uncontrollable laughter.

But it is

hardly a laughing matter when you are doing your own portrait. The experience often

leaves an uncanny effect, as though the painter was virtually creating his twin

sibling. You are staring into the mirror at yourself when doing the portrait

and afterward you will see your own creation staring back at you, solitary on a

canvas still devoid of a background. The photographer will most likely

associate the connection of the gazes, the painter’s and his creation’s, with some

sights that never fail to incite his curiosity- room within room, door opening

to yet another door, a maze of corridors promising no imminent exit. “I do not

doubt interiors have their interiors, and exteriors have their exteriors, and

that the eyesight has another eyesight,” so says Walt Whitman quite literally.

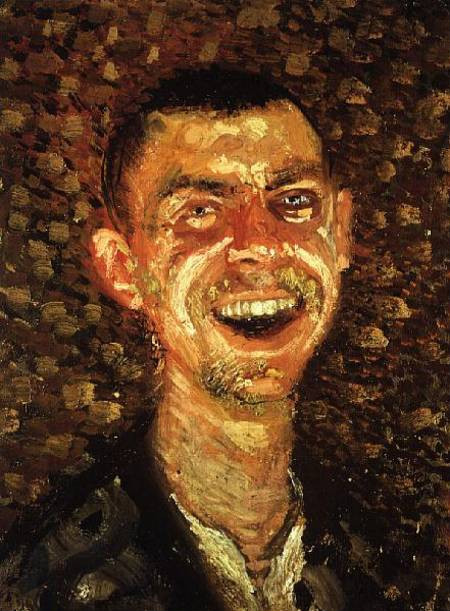

The

painter, Richard Gerstl, was one of the many Austrian artists whose portraits

are noted for their psychological insights and expressiveness. Psychology, like

sociology, is all about engagement. But rather of a more intimate engagement, psychology

plumps for a one-on-one conversation invariably conducted in a muted, wordless

manner. Therefore even when there is an expanding throng of viewers standing

before an Austrian painting, the figures in which deal with one at a time, broodingly

and patiently. Their gaze, instead of emitting shafts of blinding light that

intent on poking holes in the viewers’ eyes, breathe a cold air that envelopes

the little innocent crowd, like a lion appraising his wounded and writhing prey

from afar, before making the fatal spring.

The same

coldness permeates Richard Gerstl’s Self-Portrait

Laughing (1907), but a more expressive and menacing coldness, as the

painter is shown having a laugh, a mad and hearty laugh. The background is

composed by golden and brown daubs, as though the sky is ablaze with flying

flints. There are fires, too, burning in the painter’s eyes, but those flames do

not assume a confident ferocity. They are rather like the candles that intermittently

gutter, and spew out wax that moisten the eyes like tears that refuse to drop.

The smile

is certainly not victorious, nor does it seem to me glorious. If this is what

Gerstl reckoned as his “best face,” or at least, the face that he found the

most impressive, then he surely made no bones about his madness, or illness. But

by no means is the painter trying to elicit the viewers’ empathy and kindness

for his dismal situation. He is simply having his good, and possibly, last

laugh- at the fortune he is futile to change, at his unstable mentality he is

too disdained to seek any remedies, or at any unnamed enemies he is next bent

on destroying. The smile as all there is.

Comments

Post a Comment