"Chaos, a rough and unordered mass."- Ovid, Metamorphoses

The art of

Tintoretto aims to draw an unlikely equivalence between chaos and beauty. There

seems always a commotion going on in his paintings. Robust bodies are

confusedly tangled, insofar as one is usually convinced that the depictions are

about wars, even when most of them are not. A sense of fieriness and ferocity

is instantly felt, but that of airiness, which is a quality almost reserved for

monumental paintings like Tintoretto’s, is glaringly absent. It is curious of

how the painter had maintained, throughout his career, a predilection of conscientiously

filling up every corner of the canvas, leaving barely any spaces void.

Such

complexity of composition, however, does not render Tintoretto’s painting a

frustrating imbroglio. There is an internal equilibrium within the constant

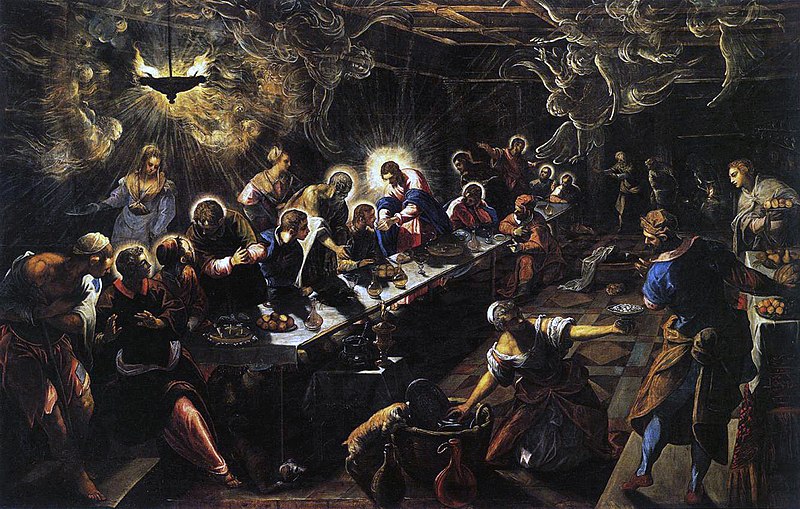

motion. The crowdedness of the scene of The

Last Supper (1592-94) is relieved somewhat by the ball of blaze above the

table, and the halos that encircle the heads of Christ and the disciples, so

that there is a marked contrast between light and shade (here the painter

presents a very crude example of chiaroscuro). Tintoretto’s version is far

removed from any typical depiction of the last supper. Besides the stock

characters, the painter also included in the feast a handful of peasants, who are

too preoccupied with their own affairs to notice anything amiss. Hovering on

the top of the scene are the ghosts, bearing down on Jesus Christ as they are

ready to summon his departing spirit. The people, the saints, the spirits- they

are all present.

To be a

viewer of Tintoretto’s work one is expected to happen on very few let-ups of

the tumultuous dramas. The painter did not need to generate chaos to excite

intense emotions. Even with a relatively sparsely populated painting like The Stealing of the Dead Body of St. Mark

(1562-66), Tintoretto can still manage to build the tension towards boiling

point. Again, there is this frenetic clutter of people in the foreground- three

men struggling to smuggle away a dead body, the heaviness of which is telling.

This is not the inert dead body one normally encounters; it retains a renewed

vigour as if the soul is still holding tenaciously on the dying flesh. A storm

is brewing- either Heavens is complicit with this ignoble affair, or the leaden

sky is the portent of an imminent retribution.

Some said

Tintoretto pioneered the most original style of Mannerism, others considered

him a baroque artist ahead of his time. The unanimous opinion, however, is that

there exists a perceptible gulf between Tintoretto’s art and that of the other

Renaissance heavyweights. The painter eschewed sensuous beauty that is common

with Renaissance paintings. Instead he exhibited with his paintings energy,

force, violence, viciousness, and so forth in the most emphatic manner. Invariably,

the subject matters are about wars, contests, the fall of the hero and the rise

of the insidious. The victory is not always equivalent to a glorious feat. In St. Louis, St. George and the Princess

(c. 1553), the princess effortlessly subdued the dragon, and is now sitting

astride the beast and glancing at the saints, her eye speaks of unmitigated

pride. The saints are noticeably mortified, with one of them throwing up his

hands- why! You just killed a dragon! One can expect very soon the princess

being severely admonished.

After

surveying Tintoretto’s oeuvre I confess I derive from it no pleasant feelings. But

I do not dismiss the truth that from time to time I find myself perversely

drawn towards the sort of beauty that is almost the antithesis of the

conventional type. This is evidenced by my abiding love for Caravaggio, most of

whose paintings, however, prompted me to avert my glance on the first sight. But

do I really take into consideration the importance of beauty when I’m looking

at paintings by Tintoretto or Caravaggio? I ask myself. Maybe not so much as

subscribing to what really matters, namely that some painters were not shy from

revealing the least savoury details of a given event. For them art is virtually

the exposure of the unvarnished truth.

Comments

Post a Comment